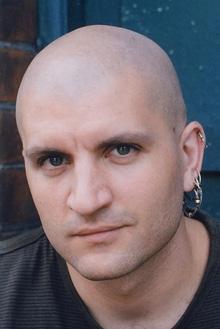

I have to confess I’d never heard of China Mieville until a few weeks ago, which was when his name popped up on a schedule of upcoming events at my place of work. It’s not everyday I get the chance to sit down and listen to another writer talk shop, so naturally I jumped at the chance. For everyone who missed out, here’s a summary of some of the most interesting points that came up in the discussion.

First some scene-setting. I’d love to say I’d read all of China’s books, but I haven’t. Not even one. As a consequence any discussion specifically relating to his novels was lost on me and won’t be noted here. If you’re a fan: sorry. Secondly, this was more of a group question and answer session (with a bit of an introduction from China himself) than a presentation or lecture. I did have a question or two in mind, but it happens they were adequately covered before I had the chance to put my hand up. Which actually worked out just fine for me.

What follows is a summary of points and phrases that jumped out at me, with a peripheral attempt at banding them together into some sort of coherent structure. Outside of this discussion, almost everything I know about China Miéville comes from this interview, dated February 2011, so you might find that I refer to some of the ideas mentioned there too. it’s worth a read: inevitably, Miéville does a much better job of summarizing his ideas about writing than I do!

Character

I find China’s approach to character development very refreshing, probably because it runs counter to much of the common advice you’ll hear and is quite similar to my own approach.

He suggests you don’t need to exhaustively plan (or, indeed, even know) every detail of your characters’ lives or the world they inhabit. Rather, the writer should approach their own work with a sense of ‘critical intuition’, which I interpret as being able to ask ‘Why is that character doing that?’ instead of saying ‘That character needs to do that’.

This really gelled me with because one of my favourite things about writing is those times when your characters surprise you, when they do something you hadn’t fully anticipated – in other words when they come to life – and if you know those characters intimately from the outset there’s very little chance of them surprising you.

This approach also reminds me of Ridley Scott’s retort to critics who complain about the ‘thin’ characterization in Alien. He points out: “You know exactly as much as you need to know about them“. And it’s true – we don’t really care about their upbringing, why they’re working on a spaceship, or what their favourite breakfast is: all we need to know is how they deal with a lethal monster being loose on their ship.

World building

Miéville’s approach to world building is, unsurprisingly, very similar.

Once again he proposes that it’s “more realistic not to explain everything” (or to know everything). to support this he provided the analogy of catching a bus in a foreign city (or even talking a walk around your own city): you’re not going to know everything about every building around you, and neither are the people with you. Why, therefore, should your narrator know everything about the world your story takes place in?

The interview I linked to at the top further stresses Miéville’s point that inserting too much detail can, rather than enriching their experience, actually take the reader out of the story. Arguably this is because the reader subconsciously understands that this omnipotent level of knowledge is unrealistic.

During the discussion, he also mentioned that writing can become ‘banalized’ by this excess level of detail. For me this comes down to the writer losing sight of the fact that they set out to write a good story and not a travel brochure. As Chekhov famously taught us if you’re going to show something to your audience/reader, then it had damn well better be important to the story otherwise leave it out (however, do also see the section on ‘words’ below).

Planning

Make no mistake: Miéville still very much advocates having a plan for your writing project.

I wasn’t certain if this was his own writing practice or just an example, but he said if you’re going to sit down and write 500-1,000 words a day then, each time, you absolutely must know what needs to happen during those words. What you don’t need to worry about so much are the specific details of what’s going to happen in three chapters’ time. I very much adhere to this because when I write I want to be thinking about the words and not about the plot: I want to get from the beginning of one scene to the end, and make sure that everyone’s in the right place for whatever happens immediately afterwards.

As an aside Miéville suggested that many brilliant novels never get written because people get so intimidated by the perceived magnitude of having to plan everything out: all those character backstories, the history of their world. I really hope more budding writers get to listen to Miéville at some point because he does a pretty good job of taking that fear away.

Of course, someone did ask specifically about how Mieville goes about planning his own work. In another point that rang very true with me, he said that his stories don’t start with a character but usually with an image; from there he likes to build up a ‘constellation of images’, which I think is a beautiful way of looking at the conceptual stage of a story.

From this constellation he likes to arrive at a flow chart which, he explained, would have a list of chapters on one side, and a list of what the characters need to do in each chapter on the other. I’m going to try that for my next big story, perhaps with a third column of ‘events’ so I can make sure the the characters’ actions and the plot correctly line up.

Words

Some of the discussion revolved around writing rules and the efficiency of prose.

China highlighted the concept (I’m not sure of the origin) that words are the window to the story: if the window becomes too clouded then it makes it harder to see the story. The window typically becomes clouded by having too many unnecessary words.

As a novice writer I’ve gone from thinking that my language has to be as colourful and descriptive as possible, to understanding that it should actually be as lean as possible, precisely so it doesn’t get in the way of the story. But then China points out: why can’t the window be a stained glass window? Again, a really nice way of looking at something from a different angle. Taken in context, I don’t believe he’s advocating reams of purple prose in your writing, but it’s not something that should automatically be ruled out.

For the record his favourite word (at the time of asking) is: ampersand.

Narrative

One last point that I’ve not reached any conclusions on myself, but is worth throwing in here, is the function of narrative.

China raised the common idea that “narrative is an intrinsic human good“. Think about it: we all assume that stories are to the benefit of society, that they enrich our lives. Miéville says that he doesn’t necessarily counter that view, but remarked that it’s something that is very much assumed and never really comes under any scrutiny.

In response to this one of the audience members (somewhat hyperbolically, in my opinion) suggested that suspension of disbelief was one of our most dangerous highs. I disagree that there’s any danger here, at least in terms of it being a high, but it did make me think about the idea of spin.

If you think about it almost any story (and let’s consider that any fact can be narrativized – a government policy, for example). Depending on how a narrative is presented, and who’s presenting it, we can come away with a range of thoughts: some to the benefit of society, some to its detriment. We see this sort of thing almost every day from creationists, global warming deniers, those opposing gun control and, of course, from those who have opposing viewpoints.

As anyone who’s used social media will be well aware, it’s quite easy to get carried away by a sense of outrage (whether you’ve experience it yourself, or observed it in others). That sense of outrage could be considered the high, and the fact that this outrage can causes you to lose that ‘critical intuition; could be seen as the suspension of disbelief. Suddenly the danger becomes quite apparent…

Anyway, I’m starting to think this is a topic for a much longer blog post!