It’s the year that I turned 12 and the year that the internet was born, at least in a purely technical sense. The first mobile phone call was also made and there was a huge ‘video game crash’ which triggered the end of Atari and was partly caused by the rise in home computing (this is the same crash that, legendarily, saw thousands of ET game cartridges buried in a New Mexico desert). Ironically the first Nintendo console also went on sale this year. In less technical news, the final episode of M*A*S*H was aired in February, garnering a massive audience of 121 million. The space shuttle Challenger launched on its first mission in April and Michael Jackson debuted the Moonwalk at a Motown celebration, causing the audience to lose their shit. If you can think of any other year that more clearly paved the way for what would follow then: answers on a postcard.

Category: Ramble Page 1 of 57

If you were to delve into the deep, dark history of this blog you’d probably find a number of old reviews. Not so much in the last few years. While I am occasionally tempted to jot down my thoughts and feelings on the movies and TV shows I’ve watched or the books I’ve read I typically find, before the idea takes hold, that I’ve already moved onto the next thing. I have decided to preserve my train of thought long enough to make an exception for Alien: Earth however, simply because it’s a TV show based on Alien which means it’s of a certain personal significance and also because it, perhaps, tells an interesting story about pop culture media in the current day and age.

1982. I hit my eleventh year. This one always feels to me like the year that pop culture really started happening. In truth it had been on the boil for a while, but with E.T. dominating cinemas, Michael Jackon’s Thriller storming the charts, and the debut of the CD this was a year of huge tentpoles for consumers to latch onto (or to be fed with until they burst). Perhaps fittingly, the first emoticons (the humble smiley) made their appearance this year. Conversely, in another sign of the old guard falling away, ABBA made their final TV appearance.

In the UK the Falklands War kicked off. Naturally I remember this vividly, albeit through the lens of a politically innocent 11 year-old. It’s strange that, in its wake, I can’t think of a single film or TV series off the top of my head that uses the war as a backdrop (note that this doesn’t mean there weren’t any—there were plenty). Perhaps as wars go it was a particularly uninspiring one.

Overall, browsing through Wikipedia, 1982 looks like a very unsettled year—lots of plane crashes, lots of political unrest, Israel once again invading other territories (Lebanon this time) and various other fairly crap things going on. So let’s ignore all that and look at some movies!!

On August 1 1981 MTV aired its first video. That video was Video Killed The Radio Star, directed by Russell Mulcahy and featuring a youthful Hans Zimmer on keyboards. MTV would change the pop culture landscape, comfortably landing its bootprint in the realm of cinema along the way, and there could be no surer sign that the eighties were coming for our films than this video featuring two people who, in very different ways, would make their stamp on movies over the next decade and beyond.

Elsewhere in the world NASA finally launched its first space shuttle, Columbia, into space following a series of test flights. I vividly remember being at school and having a routine ‘medical’ but being able to watch the launch from the surgery. Talking of medical matters, the first case of HIV/AIDS was identified in the USA—the virus became a biological boogeyman which would haunt us throughout the eighties, would claim around 100,000 lives before the decade ended, and become a vicious political hot potato causing horrific antipathy towards gay people.

I turned 10 years old in 1981 (erroneously thinking this made me a teenager until my mother pointed out that I still had a few years to go) and was just starting to get a sense of myself. I would watch Top Of The Pops every week, and particularly enjoyed Adam And The Ants at the time, and was starting to get a clearer sense of where my film tastes lay too. The eighties were waiting, and so was I.

I turned nine in 1980 and was becoming a little more aware of movies, largely through sequels to movies I’d already enjoyed. That said, the hype surrounding The Empire Strikes Back was inescapable whether you were interested or not, and most other movies at the time I became aware of because of the posters everywhere. This was also a period of my life where I’d get taken to the USA for summer holidays (perks of having a parent in the travel business) which often meant I’d get to see movies months before they reached the UK—quite the privilege back then!

In terms of other events, 1980 was the year that Mount St. Helens erupted in Washington. I wasn’t there at the time, but I was in the area shortly afterwards and remember there still being ash everywhere. It was also, of course, the year that John Lennon was assassinated. The Beatles were before my time but the shock from Lennon’s murder resonated throughout the UK in a way that we wouldn’t see again until Princess Diana’s death. It’s curious to me that the seventies effectively began with the end of The Beatles and, ten years later, the eighties begins with the loss of one of the group’s major creative forces. With Elvis gone a few years earlier it’s almost as if the eighties was determined to shed the past and bring something new.

I’m taking a personal look back at the top ten films in every year since the one I was born in. We’re up to 1979. I was cannonballing towards 8 years of age. Margaret Thatcher took power in the UK, setting the political tone for the next few decades. The Ayotollah Khomenei was restored to power in Iran. Sony released the first Walkman, and Philips demonstrated the compact disc for the first time. Usenet was created by a couple of college students who were either very bored or very smart. Perhaps both. I might remember 1979 as a particularly drab year, but change was clearly afoot. And how was that reflected at the cinema, you ask? Let’s find out.

- Alien

- Nosferatu the Vampyre

- Apocalypse Now

- The Warriors

- Mad Max

- Stalker

- Escape from Alcatraz

- Moonraker

- Life of Brian

- Kramer vs Kramer

- Kramer vs. Kramer

- The Amityville Horror

- Rocky II

- Star Trek: The Motion Picture

- Apocalypse Now

- Alien

- 10

- The Jerk

- Moonraker

- The Muppet Movie

Only four movies appear in both lists this year, which again demonstrates how our tastes change in retrospect and when marketing hype is removed from the equation. To be honest the biggest surprise to me is seeing Moonraker in the IMDB top ten as I didn’t think anyone remembered that entry with great fondness. That said, the suspiciously high showing for Nosferatu does have me continuing to question the IMDB algorithm, Otherwise I think we have a pretty good spread of movies here, showing which titles had people queuing up at the box office in 1979, and which of those have stood the test of time.

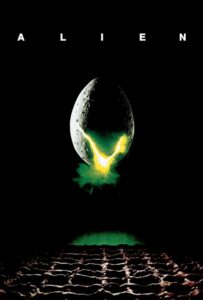

It might have started with the poster. Who could forget that haunting, enigmatic, almost indecipherable image. And the immortal tagline. An absolute masterpiece of movie poster design that conjures so many questions and delivers no answers. You look at it and you instantly want to know what the hell it means, while another part of you suggests you run; run very far away and never look back. All you know is that something is coming. Something is about to be birthed. And it’s probably going to be the worst thing you could possibly imagine.

I’m doing a personal review of the top ten (more or less—usually more) movies from every year since the one I was born. This week … it was the year we all believed a man could fly. Or perhaps you didn’t. Perhaps you weren’t even born then? Meanwhile, these days we have movie characters flying off left right and centre. It must all seem so perfectly normal. Well, if either of those are you, come with me, grab your Superman crotch popcorn bucket and let’s take a walk through the past with a recap of the top movies of 1978.

- Grease

- Superman

- The Deer Hunter

- National Lampoon’s Animal House

- Death On The Nile

- Halloween

- Invasion Of The Body Snatchers

- Days Of Heaven

- Dawn Of The Dead

- Watership Down

- Grease

- Superman

- National Lampoon’s Animal House

- Every Which Way But Loose

- Heaven Can Wait

- Hooper

- Jaws 2

- Revenge Of the Pink Panther

- The Deer Hunter

- Halloween

Let’s kick off with a few changes to the format. Firstly, I’ve tweaked the IMDB listing to only show movies that have a certain number of ratings and are above a certain score. I’m still not sure how IMDB calculates ‘popularity’ but this modest filtering will hopefully prevent the Swedish Nympho Slaves scenario from happening in future.

Second: given this is a personal reflection I’ve also opted to shuffle the way I list the movies below to vaguely reflect how significant they are to me (previously the order was roughly aligned with the chart listings). It’s never going to be as straightforward as my favourite movie being at the top and my least favourite at the bottom. Movies can be important to me without necessarily being titles I’d watch again and again. Nevertheless, you can view my ordering as a vague indication of preference.

Anyway, let’s go!

It was the year of Star Wars and The Sex Pistols—two pop culture phenonema that couldn’t be further apart which but had a lasting impact on film and music. It was a year that encapsulated escaping from things past and launching boldly into whatever was going to come next. Even NASA was playing the game, launching various test flights of its new, future-facing space shuttle. It was the year of the Queen’s silver jubilee and the UK went crazy for it; I remember street parties and celebrations. I remember my Mum dressing me up as a cavalier (cool costume!) and we went to Windsor for what I assume was the lighting of the bonfire at Snow Hill on June 6. It was also the year that I started going to see movies at the cinema.

And what was Hollywood up to …?

- Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

- Close Encounters of the Third Kind

- The French Connection

- Saturday Night Fever

- The Spy Who Loved Me

- Swedish Nympho Slaves

- Slap Shot

- Eraserhead

- Looking For Mr Goodbar

- Smokey and the Bandit

- A Bridge Too Far

- Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

- Smokey and the Bandit

- Close Encounters of the Third Kind

- Saturday Night Fever

- A Bridge Too Far

- The Deep

- The Spy Who Loved Me

- Oh, God!

- Annie Hall

- Semi-Tough

This marks the first year that I can finally access global box office stats. As such I won’t be using the North America box office top ten any more. While I expect the majority of the films that appear in the top ten will still be US-produced, I’m far more comfortable having a list that comes a little closer to reflecting what people around the world were paying to see at their local cinemas. However, there is also something a bit wrong in the IMDB top ten … which will be made plain if you inspect the number six entry up there. Given the ‘best films of the year’ is always going to be highly subjective, I think the IMDB list is as useful a barometer as any even if there’s something a bit skewiff with its algorithm. Either way, using both list allows me to see how the most popular contemporary films of the year relate to the most popular retrospective films of the same year.

1976 was the year of the big summer heatwave in the UK, which I have a vague memory of as “that one time we actually got summer”. I expect I spent a lot of time in my paddling pool. It was also the year that Apple Computer Company formed and released its first computer (handy, given their name) and a space shuttle called Enterprise was unveiled. Like the real Enterprise it couldn’t actually go into space, but it was a cool bit of publicity all the same. Meanwhile, the UK and Iceland ended that third cod war, much to the relief of political superpowers across the globe.

- Carrie

- Taxi Driver

- The Omen

- Rocky

- Logan’s Run

- Murder By Death

- All The President’s Men

- The Enforcer

- A Star Is Born

- Midway

- Rocky

- To Fly!

- A Star Is Born

- King Kong

- Silver Streak

- All The President’s Men

- The Omen

- The Enforcer

- Midway

- The Bad News Bears

For a while there I thought 1976 might be the year I finally saw some of these movies in the cinema: I distinctly remember watching King Kong and The Pink Panther Strikes Again on the big screen. However, given both of these movies were released on Boxing Day 1976 in the UK I very much expect I wouldn’t have seen them until the subsequent year (remember, movies hung around a lot longer back in those days!)

While neither of those movies are particularly memorable, it was otherwise an exceptionally solid year for cinema—just look at that IMDB top 5! And plenty of quality picks lower down in the list too. Let’s get into it.